White House thrillers have been a staple of the suspense genre for decades, and many films and television projects have added to their number. But none have done so with an actual president doing the writing.

Former President Bill Clinton and bestselling novelist James Patterson have collaborated to write The President Is Missing, a political thriller following a president and his team trying to stop a cyberterrorist plot.

When radical mercenary Suliman Cindoruk designs a catastrophic internet virus targeting Americans, the only people standing in the way of its activation are two former allies of the terrorist and President Jonathan Duncan. To make things more stressful, Bach, a cold-blooded assassin, is determined to take out the president.

Author Roy Neel (President Clinton’s former deputy chief of staff) speaks with both remarkable authors about their partnership and the project.

Roy Neel: You’re both storytellers. How did you get started writing The President Is Missing?

James Patterson: We have a mutual agent, who thought it would be a great idea to do a book together. But Mr. President, you should tell the story.

President Bill Clinton: I thought it was a great idea, but I didn’t think Jim needed my help to be a successful writer.

JP: One of the things that was important to me was that it not come across as a James Patterson novel, but a Bill Clinton and James Patterson novel. I can make stuff up. I have a good imagination, but the president has been there. You just can’t find that authenticity in any thrillers or novels today.

People read political thrillers, watch “24” or “Homeland” or some other television show about terrorism and think, “Well, that was entertaining, but it’s unrealistic.”

BC: I like those shows, but one of the things that struck me is that we’ve wound up with the worst of both worlds. When it came to the real threats, when politicians were out killing people, it’s kind of jaded them about everybody who’s in this business, which I think is also misleading.

JP: One of the things we’d like to communicate with the book is just how serious and tense and difficult this job [of president] is. In between “Saturday Night Live” and some of these shows like “House of Cards,” which start getting crazy, we stop taking that job seriously. If we don’t, anything can happen when we start talking about who should be the next president.

The President Is Missing deals realistically with the burden of presidential decision-making. President John Duncan can bring in unlimited advisers during this crisis, but in the end, it’s all on him. Mr. President, you must have channeled that experience in creating the character.

BC: I tried to. I also tried to show how important it is to have the right people helping you in that situation, and how dangerous it is if you don’t. I don’t know how many times you were there, Roy, when Al Gore and I would talk about some security issue, and he’d actually go get the original intelligence data and review what the CIA had written. It matters: what you do and how it affects people.

Mr. President, you faced this issue during your time in office, as cyberterrorist technology was in its infancy. And now, we see almost daily events where corporate and government networks are compromised, with data stolen from millions of consumers. Not to mention the Russian interference into the 2016 election and reports of state-supported computer hacking from North Korea and China.

BC: Roy, you were in the White House with me 21 years ago when I issued the first executive order to set up a special group on cybersecurity. We made a good beginning, but we had no idea then what the almost limitless possibilities were for mischief and trouble. I don’t think we’ve done enough about it. Maybe one of the things that will come out of this book is the heightened interest in the issue.

JP: There are two chapters where Augie [a Suliman protégé] talks to the assembled group about what can happen. I think they are two of the scariest thriller chapters ever written, because they lay out what can happen. And we’re not prepared for it. So as the president said, this is a little bit of a warning shot for the country, because we’re not prepared.

I can recall sessions in the Oval Office that played out a lot like those in The President Is Missing. I heard your voice in so much of the fictional President Duncan. In the opening chapter there’s a great thrashing of an opposition speaker of the House who is a thorn in the president’s side. That must have been fun for you to write.

BC: I got tickled about that.

JP: That was fun. To the point that the reader is going to say, “Come on, this isn’t going to happen.” But we show how it did happen and why it would happen.

BC: We really worked on all that. Not just to be authentic about physical settings and established procedures, but really how the decision-making process really works when it works well, and when it breaks down.

You’ve created many strong women in key roles in this book—Carrie, the chief of staff; Liz, the FBI director; and others. Is there a message there?

BC: Each of these women was qualified. That was really important to me. Intelligent and able. I wanted to make the point that this was an empowerment group. Nothing was given to them—they earned it.

JP: And not afraid to show in a couple cases that they were flawed.

Mr. President, it must have been liberating to write in a fictional medium about so many things you’ve worked on and been concerned about for so long.

BC: Yeah, I loved it. You know, I’m a big fan of mysteries and thrillers. I consume a lot of them, including a large number of Jim’s books. I always wanted to write one, but I never got around to it. I felt a lot of confidence working with Jim. He’s a good storyteller and knows how to get from A to B. I loved the whole process and loved working with him. I loved the fact that he would say we needed more on this or that. And I could say, “It wouldn’t happen that way, it would happen this way.”

JP: What I hoped to do here was to write the best thriller ever written about a president. And I knew I had an advantage because I’d be working with the president, who, as you said, is A) a great storyteller, and B) knows what goes on in that office. I’ll leave it up to readers about whether we compare to Advise and Consent or Seven Days in May or The Manchurian Candidate.

Roy Neel was President Clinton’s deputy chief of staff and longtime chief of staff for Vice President Al Gore. He is the author of the political thriller The Electors.

Author photo credit David Burnett.

You explore mental illness in empathetic and unflinching depth in your book—from Miranda’s and Kate’s perspectives as they suffer and attempt to find peace, as well as from the viewpoints of those who care about them and attempt to provide help. What was most valuable for you as you researched and created these characters?

You explore mental illness in empathetic and unflinching depth in your book—from Miranda’s and Kate’s perspectives as they suffer and attempt to find peace, as well as from the viewpoints of those who care about them and attempt to provide help. What was most valuable for you as you researched and created these characters?

High Place is almost a character in itself in this novel. Were you inspired by an actual house or location or was it purely a place in your imagination?

High Place is almost a character in itself in this novel. Were you inspired by an actual house or location or was it purely a place in your imagination?

There’s an obvious theme in the book about the pressures and expectations others put on a person, especially a star athlete like Dylan. His brother, Joel, is a gay man and faces his own prejudices. What compelled you to write about those pressures, and what lessons do you hope readers might take away from this novel?

There’s an obvious theme in the book about the pressures and expectations others put on a person, especially a star athlete like Dylan. His brother, Joel, is a gay man and faces his own prejudices. What compelled you to write about those pressures, and what lessons do you hope readers might take away from this novel?

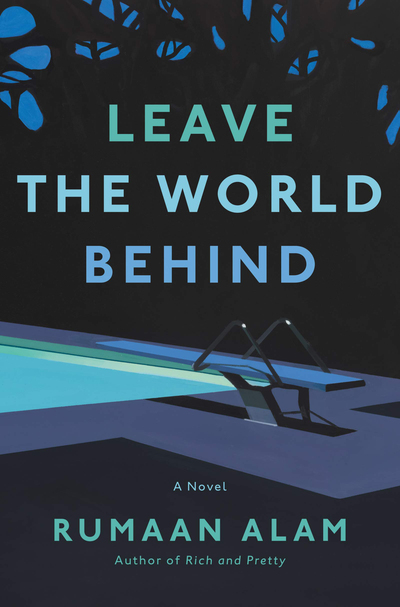

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Your approach to Emmy is so clever: an Instagram influencer who draws a million-plus followers by making her life seem worse, not better, than it is. Do you think people will reevaluate those they follow on social media, and why they follow them, after reading your book?

Your approach to Emmy is so clever: an Instagram influencer who draws a million-plus followers by making her life seem worse, not better, than it is. Do you think people will reevaluate those they follow on social media, and why they follow them, after reading your book?