When I finally let my mother read Struts & Frets, she called me up and said, “I’m not an alcoholic.”

“Mom, it’s fiction,” I said.

“Well, I was going to buy a bunch of copies and put them in my waiting room, but I don’t see how I can do that if the mother character is an alcoholic therapist. People might think it’s about me.”

After my friend Ryan read Struts & Frets, he asked, “Why did you make me gay?”

“It’s not you,” I said.

“Is it supposed to be Zach, then?”

“Dude, it’s fiction.”

It seems a lot of people want to know where that line is between fiction and reality. But honestly, in my mind there is no clear line between them. Most stories occur to me as a thought exercise. A “what if” question. It can be as simple as, “What if my grandfather had decided to pursue his passion for music professionally instead of becoming a dentist?” A story like that might have many similarities to my own life. Or the question could be, “What if I were a teenage girl who discovered on her 16th birthday that her mother was a demon?” Clearly, it’s unlikely there would be as many obvious similarities with my own life. But I see no true difference except in degree. I beg, borrow or steal from my own life as needed. I take two people I know and mash them into one character. I take events from one period in my life and plant them in another. I exaggerate, fabricate, idealize, deconstruct or destroy whatever is necessary to follow the story to its conclusion.

In Struts & Frets, the main character, Sammy, says this about writing: “I tried to look at writing a song almost like solving a mystery. The song was there, buried somewhere in my brain. All I had to do was follow the clues until I figured it out.”

I don’t agree with Sammy on everything, but on this we are alike. Because I do believe that all these stories, and all these characters, are somewhere inside me, just waiting to get out. I think that is true for all of us, to a greater or lesser degree.

I think this belief comes from my background as an actor. In particular, a character actor. Back when I was studying acting in college, whenever a director said, “Hey, we need a punk hunchback clown who suffers from Tourette’s,” or “Hmm, this play calls for a transvestite junkie hooker,” the follow-up question was often, “What’s Skovron working on right now?” Well, OK, that’s not really true. Usually they would first ask, “What’s Zachary Quinto working on right now?” and if he was unavailable, I would do in a pinch.

Being a character actor really means that you cannot be typecast, and therefore go into the miscellaneous bin for casting. While that was frustrating at times, it also made things very interesting. I had to be so many different, contrasting people. I had to find a part of myself, no matter how small or warped, that I could use to bring some authenticity to the bizarre procession of roles I played throughout my brief career on the stage.

A few years of playing some of the most outlandish characters imaginable made me rather flexible when it came to the concept of identity. Inevitably, I had to ask myself: while these other “selves” were not real, did that make them any less true? I have not, and will not ever, marry a Chinese man thinking he is a geisha, and yet when I played René Gallimard in M Butterfly, my performance resonated with the audience in a way that no retelling of my real life could have. I don’t think performing a series of pratfalls and pantomime while discussing remuneration in iambic pentameter would win me many friends at the office, but when I did that as Costard the clown in Love's Labour’s Lost, the audience thought it was hilarious.

So is it artifice? Whether it’s fiction or theater, am I lying to the audience in a pleasing and entertaining way? Or am I just telling a different kind of truth? One that is not so caught up in the technicalities of what actually happened, but more captures the spirit of what was, is, or could be possible, if only we would open ourselves up to it.

In the end, does it matter which events in a piece of fiction actually happened, as long as the story rings true? Ralph Waldo Emerson had this to say: “Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures.”

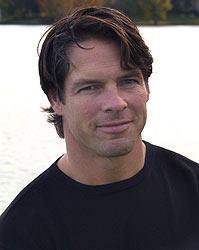

Jon Skovron is a music geek who can play nine instruments, but none of them well. Struts & Frets is his first novel. In his spare time, he writes technical manuals and tries to forget about his sordid past as an actor. He lives with his wife and two kids outside Washington, D.C.