A cultish group is one that promises to improve your life if you follow its regimen, buy its products or obey its leader. In Cultish, Amanda Montell peels back the linguistic layers of these groups and demonstrates that even mainstream brands and organizations use “cultish language” to draw people in.

Your father spent part of his childhood in a cult; more recently, your close friend joined Alcoholics Anonymous. How did these two loved ones’ stories prompt your interest in how cultish groups use language?

I grew up on my dad’s absolutely riveting tales of the four years he spent in a notorious socialist “utopia” in the Bay Area called Synanon, which started out as an alternative drug rehabilitation facility and later came to accommodate “lifestylers” who just wanted in on this unique communal way of living. (My dad joined in 1969, totally against his will, thanks to his communist absentee father, who was kind of a pseudo-intellectual hippie.)

To me, the most fascinating part of my dad’s stories was the special language they used in Synanon—buzzwords, slogans and terms that would sound utterly inscrutable to an outsider (like lifestylers, for example). The language was clearly meant to separate members from the outside world in a powerful psychological way.

Years later, in early 2018, I was talking to my best friend, who had just started going to AA, and I was equally bewildered by the sheer robustness of AA’s lexicon. AA is obviously a very different kind of “cult” than Synanon was, but that conversation with my friend prompted me to wonder: How exactly does cult language work to lure people into fanatical fringe groups? How does it make them stay?

Why do you think cults are a pop culture obsession at the moment? (The Girls by Emma Cline, Godshot by Chelsea Bieker, “The Path,” the “Escaping NXIVM” podcast, etc.)

In American culture now, much like in the 1960s and ’70s (another peak cult era), we’re experiencing a great deal of social tumult and mistrust of mainstream institutions such as government, religion and health care. So we’re looking to alternative sources to fill these voids.

At the same time, since the 1970s, dangerous cults (as well as relatively harmless “cult-followed” groups) have taken on a sort of perverse vintage cool factor. Fringe groups are spooky and fascinating, but they’re also very much afoot in our culture right now, so we find ourselves falling down these culty rabbit holes, unable to look away, almost like a car accident. We’re rubbernecking, scanning these stories to tell whether or not these groups are a threat to us. My argument in the book is that to some degree, we’re all under cultish influence. The proof is in how we speak every day.

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Read our starred review of Cultish.

How many cult survivors did you interview for this book? How did you find them?

Oh gosh, dozens and dozens. Not all of them made it into the book, but the conversations were all enrapturing and invaluable. I met them all sorts of ways. Some I came across in documentaries or in articles, some I already knew or was connected to through friends, and some I just met at parties around Los Angeles (which I think says a lot about this town). You can’t go to a dinner party without running into some dreamer who was in Scientology or Kundalini yoga or at least some sort of pyramid scheme.

Why are phrases like brainwashing or mind control insufficient to describe how people get involved in cults? Were you surprised that the experts you interviewed said they don’t find those terms useful?

This was one of my first and favorite discoveries of the book. Popular media tends to explain how people end up in cults by talking about brainwashing, but I learned from cult scholars like Eileen Barker and Rebecca Moore that brainwashing is nothing but a metaphor (no one cuts open the brain and scrubs it clean) and a pseudoscientific concept (you can’t prove brainwashing doesn’t exist). In fact, using the word brainwash often does nothing but morally divide us: “You’re brainwashed!” “No, you’re brainwashed.” Once shots like these are fired, they choke the conversation, making it impossible to figure out what actually motivates people to become involved in cultish ideology, which is a much more interesting question and the one my book aims to answer.

You were previously a beauty editor at a women’s interest website and saw firsthand how the beauty, wellness and fitness industries use cult in marketing-speak (e.g., “a cult favorite”). What’s your take on that kind of usage?

I actually don’t think it’s harmful or offensive to use cult as a sort of hyperbolic metaphor in a marketing context like this. Linguists have found that we as speakers and listeners are generally quite good at assessing the meaning and stakes implied whenever a familiar word is used in natural conversation. So when people liken a beauty brand to a cult, few listeners are going to become concerned that there’s a manic preacher making all these lipstick consumers engage in satanic rituals or something.

The only challenge with the word cult is that it’s become so broad, judgment-loaded, sensationalized and even romanticized, and is used in so many different contexts, that it really has no official or academic definition. In fact, many of the cult scholars I spoke to for the book don’t use the word formally, favoring more specific terms like new religions or alternative religions instead. The word cult has become kind of useless when describing groups that are actually dangerous, because it’s so unspecific. I think this haziness surrounding the word cult also says something about our culture’s extremely weird relationship with community, spirituality and identity.

“How exactly does cult language work to lure people into fanatical fringe groups? How does it make them stay?”

How is elitism—wanting to be part of the in crowd—exploited by cultish groups?

Life as a human being is extremely confounding, and most of us spend a great deal of our time searching for satisfying answers to life’s biggest questions. When a guru or leader promises that they have the answers, and that you are special and smart enough to access them, that’s a really compelling message.

It’s a stereotype that cults or cultish groups prey on the weak and needy. But in fact, research shows that cults usually exploit people who are idealistic, optimistic and hardworking—people who don’t give up when things get tough. How can someone’s idealism, optimism and good intentions become the inroad to cultish groups?

Those are the types of people that cult recruiters actively go for. They don’t want people who are liable to break down quickly or get antsy and quit right away. Being an active member of a cult is hard work, so they want the best and brightest—people who hopefully have money to spare, are service-minded enough to give it to the group, and have enough optimism and perseverance to remain loyal even after things inevitably go sour.

As a linguist, what is the difference between a religion and a cult? Did researching Cultish make the boundary between the two seem more or less blurry?

A Jonestown survivor I interviewed for the book said something funny to me. He said, “A cult is like pornography. You know it when you see it.” It’s a pithy and humorous aphorism, and it totally rings true, but in terms of actual social science, instinctive judgments like that are not how one tells if a group is dangerously culty or not.

There’s another quote I included in the book, which I think is more logically sound. It comes from the religious studies community, and it goes, “Cult + time = religion.” Cultural normativity has so much to do with whether or not a spiritual group is considered a cult, even if its tenets and behaviors are no wackier or more dangerous than a better-established religion. After all, in Catholic Belgium, Quakers are considered a deviant cult, and Quakerism is just about the chillest religion around.

“A cult is like pornography. You know it when you see it.”

The word gaslighting is used frequently online and in media. What does it really mean, and what does it have to do with cults?

Gaslighting is a term that derives from the 1938 British play Gas Light, which chronicles a husband’s attempts to drive his wife to madness in part by dimming the lights in their house and then denying that anything is different when she points out the change, causing her to doubt her own sanity. Today, gaslighting is used metaphorically to describe any situation in which someone tries to force another person to question their own completely valid, grounded reality as a means of gaining and maintaining control over them. It’s a tactic employed by not only toxic romantic partners (who are more or less leaders of their own minicults) but also cult leaders, who thrive on causing followers to mistrust their own thoughts and feelings so that they depend on the leader to tell them what they need to do to feel safe. In Cultish, I talk all about how to recognize gaslighting in language. (The section on Scientology is particularly disturbing. Those folks are the ultimate linguistic gaslighters.)

Multilevel marketing (MLM) and direct sales have a long and ignominious history of targeting women, especially stay-at-home moms. How have more recent MLMs such as LuLaRoe employed phrases like boss babe and entrepreneur to their benefit?

Multilevel marketing (MLM) and direct sales have a long and ignominious history of targeting women, especially stay-at-home moms. How have more recent MLMs such as LuLaRoe employed phrases like boss babe and entrepreneur to their benefit?

MLMs have always preyed on folks locked out of the labor market, especially unemployed middle-class wives and mothers. Since the dawn of the modern direct sales industry, MLM recruitment materials have employed pseudo-female empowerment language as a way to “inspire” (read: deceive) potential “affiliates.”

In midcentury America, Tupperware promised to be the “best thing to happen to women since they got the vote.” Now, in the era of Lean In commodified feminism, these insidiously nimble companies use trendy, Pinterest-y #girlboss language as a way to convince women that they’re signing up to be the SHE-E-O of their own business, as opposed to just another cog in the predatory wheel of multilevel marketing.

What are some of the features of cultish language used by Q, the supposed leader of QAnon? What was it like writing and editing this book while QAnon rose to prominence?

The language of QAnon has now spread far beyond the terms initially used by the group’s faceless “leader,” Q. QAnon has since melded with New Age wellness communities and anti-vax/anti-mask circles, so the language has several dialects, if you will. It’s basically a weird hybrid of conspiratorial speak (“deep state,” “liberal elite,” countless code words, acronyms and hashtags) and woo-woo talk of “vibrations” and “great awakenings.” And it’s always changing, in order to accommodate new QAnon offshoots and to outrun social media algorithms, which become trained to recognize QAnon language and disable the accounts using it.

It was interesting, to say the least, to write about QAnon as it was taking root and then exploding and evolving; it required a lot of last-minute updates. Actually, the final part of my book was about something entirely different before it became clear that QAnon was becoming a big deal. I’m saving the content that got cut for a rainy day.

“None of us is above cultish influence, not even me.”

Jeff Bezos is known to use vague aphorisms such as “think big,” “dive deep” and “have backbone” as Amazon Leadership Principles. Self-help bloggers on Instagram tend to embrace similarly vague “You can do it!” messages. What sets off your alarm bells when you read these types of so-called inspiring messages?

I think fauxspiration can be more sinister than it sounds. It’s the sort of language that triggers a strong emotional response in people, but it doesn’t actually mean anything specific, and cult leaders benefit from that vagueness. When their rhetoric is lofty and nebulous, ill-intentioned gurus can hide pernicious intentions or even change their fundamental ideology whenever it’s convenient, and meanwhile, people will just project whatever they want the language to mean onto it.

One example of how this can play out in a dangerous way is in the form of the fauxspirational quotegrams that the “Pastel QAnon” community uses. A Pastel QAnon person might post a millennial pink cursive post that says something like, “You have the power to raise your own vibration,” which may not sound like a culty message to outsiders (we “sheeple” can be so “blind”), but those who are already amenable to New Age-y conspiratorial thinking might interpret that to mean “You don’t need pharmaceuticals to heal your depression or the vaccine to protect you from COVID.”

Toward the conclusion of Cultish, you say that writing this book led you to have a “stronger sense of compassion” for people who get involved in cultish groups. Why is that?

Ironically, when talking about cults and cult followers, a lot of us do the same thing that people in cults are trained to do, which is to morally and intellectually separate ourselves from those people. We like to tell ourselves that folks who wind up in cultish groups, from NXIVM to QAnon, are naive, messed up idiots and that we would never get involved in a group “like that” because we’re too smart and virtuous.

But I’ve found that oftentimes the people who are the most judgmental of cult followers (which, again, is a subjective term) are people who are involved with pretty culty groups themselves—whether it’s a startup that puts the “cult” in company culture or some all-consuming online community. None of us is above cultish influence, not even me. And in general, I find that understanding the psychological motivations underlying people’s seemingly bizarre behaviors makes you feel calmer and more compassionate. Knowledge is power, but knowledge is also empathy. And that’s ultimately what I hope my book does for people.

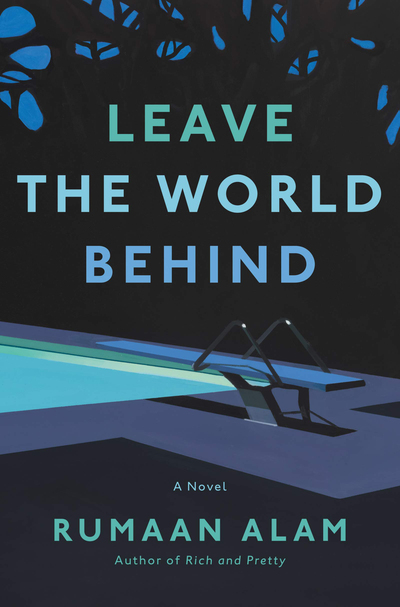

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Much of the dread, confusion and fear in Leave the World Behind comes down to technology: The internet is down, and the radio and TV aren’t working. Alam knew that readers would relate to the experience of having a bad Wi-Fi connection or their cellphone being out of range. But we also trust these devices to eventually reconnect. What if they didn’t? For the characters in Leave the World Behind, frustration at the lack of concrete information soon turns to panic. Speculation replaces fact. The terror lies in the unknown.

Your undergraduate thesis was a biography of David Foster Wallace. What did you learn (either emotionally or practically speaking) about researching a person’s life and death from doing your thesis?

Your undergraduate thesis was a biography of David Foster Wallace. What did you learn (either emotionally or practically speaking) about researching a person’s life and death from doing your thesis?

Multilevel marketing (MLM) and direct sales have a long and ignominious history of targeting women, especially stay-at-home moms. How have more recent MLMs such as LuLaRoe employed phrases like boss babe and entrepreneur to their benefit?

Multilevel marketing (MLM) and direct sales have a long and ignominious history of targeting women, especially stay-at-home moms. How have more recent MLMs such as LuLaRoe employed phrases like boss babe and entrepreneur to their benefit?