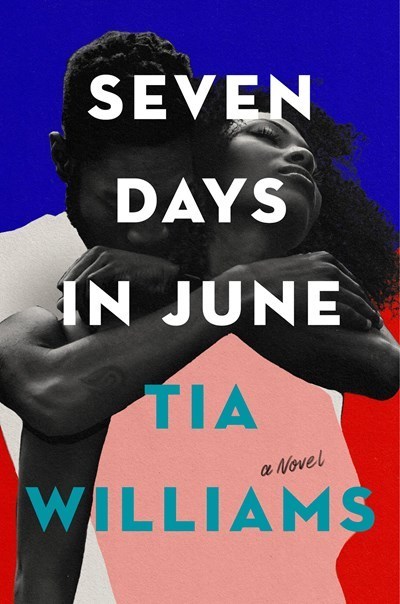

“Grown women knew better than to attach themselves to time bombs. Teenage girls couldn’t wait to be ruined.” So writes Tia Williams, author of the smart and steamy Seven Days in June. The “grown woman” is Eva Mercy, a 32-year-old romance novelist and single mom in Brooklyn. The “time bomb” is Shane Hall, a literary novelist and former paramour who unexpectedly reappears in Eva’s life at a book festival. The Black literary world doesn’t know that Eva and Shane were teenage lovers—or that they’ve been communicating to each other through their books for years.

ALSO IN BOOKPAGE: Summer reading 2021: 9 books to soak in this season

Seven Days in June is a slow burn as Shane and Eva attempt to heal old wounds, their love affair made all the more delicate by Eva’s history of abandonment. Chosen family is a strong central theme in the novel, and characters like Eva’s spunky daughter, Audre, and book editor, CeCe, bring warmth to the pages. But this isn’t a light romance by any means, especially during flashbacks. Shane entered foster care as a child and is now in Alcoholics Anonymous. Eva has a history of self-harm, and an early scene depicts an attempted sexual assault.

In addition to addressing mental health concerns, Seven Days in June portrays the daily difficulties of having an invisible disability. Eva has experienced migraines since she was young, and she still struggles to manage them without revealing her pain to the world. But Williams never uses Eva’s illness to inspire pity or to cast her as somehow weak. It’s refreshing to see a character whose disability is fully developed and integrated into the narrative from start to finish.

Through this gripping love story, Williams reckons with family histories and shows the power in rewriting our origin stories. She lays bare what happens when we are “fearless enough to hold each other close no matter how catastrophic the world” becomes. Readers will feel as attached to these characters as Eva and Shane are to each other.